It is the the one-year anniversary of Laura Barns’s suicide. She shot herself in the face in front of the school baseball field while onlookers both begged her to stop and filmed the event on smart phones. Her past life remains on the internet – her Facebook profile is still intact, and people post on her wall in memorial; her suicide video remains viewable on a streaming video site with sketchy content regulations; a YouTube video shows her embarrassing drunk antics at a party with the title “LAURA BARNS KILL URSELF.” A group of friends gather on a Skype video call to hang out with each other and plan for an upcoming party, however there is an unknown user in this gathering who cannot be kicked out, has unique control of their technology, and begins a methodical online torture of this group of teenagers. Levan Gabidaze’s Unfriended (2014) is a supernatural horror film that focuses on a group of high schoolers who each played a part in driving Laura Barns to suicide and her vengeful spirit that haunts them from within the internet and their bedrooms. Laura’s ghost (referred to further as just the ghost, spirit, and etc.) transfers itself across many forms and platforms – it is present in different instant message services (Facebook, Skype), manipulates people’s computers within the operating system, glitches across buffering webcam streams, in the bedrooms of the various teens, and as a hardware corruption that signals the cues of pending death.

Distinct in its construction, Unfriended takes place entirely within Blaire’s (Shelley Hennig) laptop screen. It is not a camera pointed at the screen from within her bedroom, but the digital representation of the screen itself. Cinematic scenes shift as Blaire shuffles between browser tabs and various program windows, but the screen itself never cuts or stops presenting diegetic action. The characters (including Blaire’s image) exist in small streaming webcam boxes, but we hear the clicking of Blaire’s mouse, the typing of her keyboard, and her voice as extradiegetic elements – audio elements removed from the digital representation of Blaire’s desktop and its interactions with various programs and internet elements. The ghost is not limited to these spaces. It is not in one bedroom, one computer, nor limited to its view of one particular screen. The ghost is presence (binary data, a “user”), absence (never directly seen or experienced), and corruption (glitches or errors that technology cannot manifest and supernatural elements that humans cannot comprehend). The audience is placed in the position of participant, as they are looking directly at the view of a computer screen, as if it were the view of their own. Layers of reality are compressed allowed diegetic reality, the supernatural, and the audience’s experience to exist simultaneously. As a non-dimensional force unbound by traditional logics, the supernatural is able to transition the spatial elements that serve as a structure for the film’s construction, narrative, and reception, presenting a possibility where horror is not limited to the diegetic constraints of the cinematic experience.

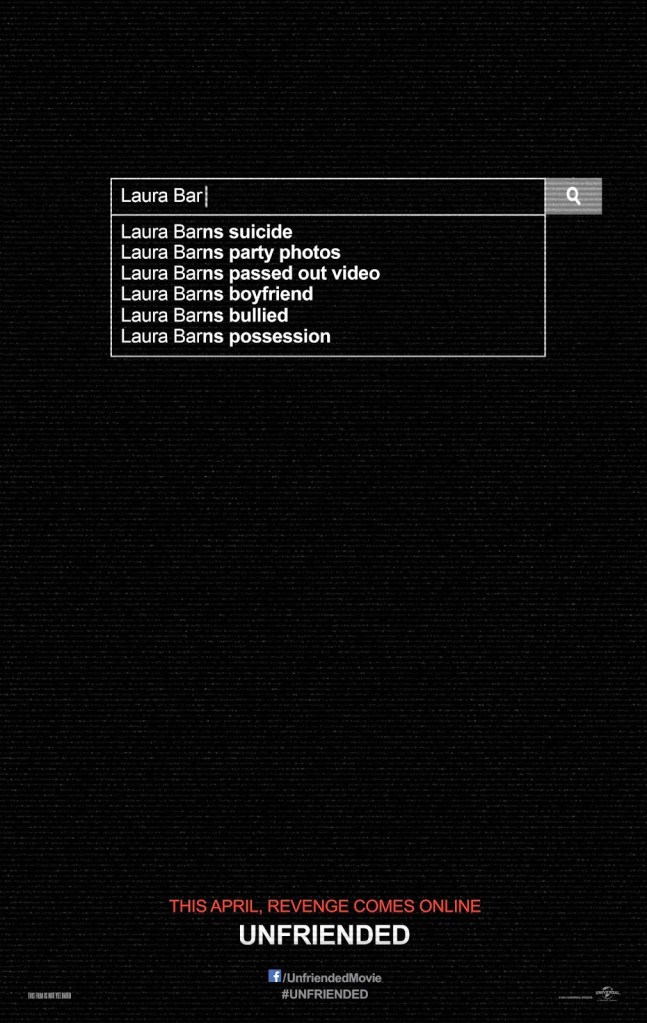

Poster from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unfriended

As the film opens, the audience sees the Universal Studios logo span into frame. As the image of Earth rotates in the emptiness of space, the cinematic image on screen begins to glitch slightly. This is a cue to the audience of what is to come, but also serves as potential confusion in a world of digitally displayed images. The corrupt image and accompanying audio is commonplace among viewers in an age of digital content. There is a lag in bandwidth, too many things are going on at one time, a website’s server is over taxed – the variety of reasons for errors are numerous and the digital error can be mistaken as commonplace and it is quickly corrected as the audience soon sees the image of a computer screen. This transition is jarring, as there is no title sequence or opening credits, forcing the audience to immediately focus on the film, making it all the easier to forget the digital error they just witnessed. We see the desktop of an Apple computer and its familiar operating system scattered with photo files, folders, and various programs. Program windows layer over the screen and on top is an internet browser looking at a warning screen at LiveLeak.com – “Warning – Laura Barns suicide might contain content not suitable for all ages. By clicking on continue you confirm that you are 18 years and over.” A loud mouse clicking noise approves of the content and the audience sees an image of a teen girl in the distance. A crowd of panicked people are yelling over loud, gusting winds. Nothing is clear until we hear the gunshot. The computer user clicks on a link on the video’s description – “The video that forced her to kill herself is still online here.” We are redirected to a YouTube video with over 75,000 views and the audience gets only a snippet of Laura’s drunken behavior at a party (which continually extends throughout the course of the film) before a Skype call interrupts the stream. On the anniversary of Laura’s death, Blaire accepts a video call from her boyfriend Mitch, and this call is soon to be overrun by several of her friends and a mystery participant.

It is this with video call that we first experience the video and audio distortion accompanied by the ghost of Laura Barns. As Adam asked Mitch who the unknown “friend” in the chat is, an audio distortion provides slight noise, as if dialing into an accurate radio station or plugging in a live speaker cable. When a person acknowledges the presence, their video and audio distorts within the group chat. The user is not typing, and its webcam image is turned off. As Blaire attempts to hang-up on the user, slight pulses of static are heard. The friends assume it is a random mistake and continue on with their night. As Blaire and Mitch chat privately outside of the group, the two both get Facebook messages from Laura Barns’s account. While the mysterious Skype user is initially unknown, this Facebook message is the first iteration of the ghost and it manifests itself through an alert bubble and IM bloop sound on Blaire’s computer. An alarmed Mitch links Blaire to a message board dedicated to the paranormal, warning people not to accept messages from the dead, and describing how vengeful spirits can force you to kill yourself. It is after this discovery of potential power that a new noise is heard, that of a clicking hard drive disk. As Laura’s Facebook account is shown to be “typing” a message in response, these noises persist. While some noise is normal of a hard drive processing data, its volume and striking quality bears resemblance to what is known in computer technology as “The Click of Death” – a physical error where a hard drive disk cannot read corrupted sectors of data (Gibson Research Corporation). This noise occurs when Blaire’s mouse cursor hovers over Laura’s name or other textual elements related to the supernatural and clicking increases in ferocity in relation to the ghost’s presence. When the ghost is “there,” the clicking occurs on its own accord. This soon invades the group’s video chat (“Well, the glitch just typed!”) and friends all have to engage with the vengeful spirit of their dead friend.

As the ghost begins to threaten Val, a dog begins to bark furiously off camera. While the clicking of Blaire’s hard drive is an immediate noise heard by the audience (as Blaire is wearing headphones), the dog’s barks are another way in which the presence is aurally manifested. After Val’s suicide, the ghost begins systematically eliminating the rest of the friends. Some are dealt with because they are trying to stop the ghost’s revenge, but most are forced into suicide because of their involvement with events that lead to Laura’s death. Blaire attempts to call emergency services, but the operator speaks with the will of the ghost, forcing her to hang up the phone. This leads to a game of “Never Have I Ever,” where the friends must confess to various acts (after five confessions, you will die). The ghost uses a group chat to bring up parts of Laura’s death and various instances proving that the group of friends is not as wholesome as they appear. While some turn on each other in an attempt to extend their own lives, it is clear that the ghost is in control of the situation. When Blaire is the only one to remain, the ghost’s control is dominant. It plays songs on Blaire’s computer, signaling her end. The hard drive cycles and clicks with taxed effort and pending failure. On Facebook and Instagram, the rest of the kids at the high school soon learn the ultimate truth of the events leading to Laura’s death, as an instant message proclaims “What u’ve done will live here forever.” In the film’s final seconds, Blaire’s computer is slammed shut by dead fingers, and we see Laura’s ghost for the only time.

The barking of the dog, the glitching noise of a buffering audio/video stream, and the noise of degrading hardware all represent instances of awareness of the supernatural. This demonstrates multiple diegetic layers present in the film. As the film takes place in the digital environment of Blaire’s computer screen, nearly the entire film exists as diegetic content. Blaire will occasionally play a song on iTunes or Spotify, a YouTube video disrupts the narrative, and program windows shuffle over top of each other to transition between scenes. There is no camera gaze per say, as the view is not of Blaire’s computer, but the visual representation of the screen itself. Though we are at Blaire’s computer, we only see her through her own Skype webcam image in the group’s chat. Only particular audio exists outside of the digital screenshot – Blaire’s voice, the sounds of her mouse and keyboard, and the hard drive clicks associated with the ghost. While Blaire is the source of the former, the latter clicking exists on its own. Because of her earbuds, she cannot hear the noise her computer makes, and so the ghost’s presence in the form of this type of audio is something only the audience would be able to discern. Extradiegetic information exists for the audience, and if Blaire is not the source and cannot hear the clicks, then this audio represents an extradiegetic layer of cinematic information. When the chat’s stream is interfered with by the ghost, it glitches both visually and aurally. This diegetic is a diegetic representation of the ghost’s presence, as the friends sometimes acknowledge this form of glitch. The audience is to gleam that the dog is barking at the presence of the ghost, and that barking exists within the audio of the Skype chat. The hard drive clicking noise represents something else – a transition between the digital and physical a transition between diegetic and extradiegetic representations of narrative. The ability to cross these boundaries of spatial and temporal dimensions and representations emboldens the film’s supernatural possibilities, and only the ghost is able to possess that form of power over the film and the audience.

Within the horror genre, supernatural space exists separate from and in relation to the diegetic realities of the film. A knowledge, force, or entity creeps its way into our understanding of the world around us, imposing fear and horror along the way. As such, the genre hinges on the paradox of contrasting knowledges and experiences of assumed dominance by human agents. This essential aspect establishes the genre as “a privileged site in which this paradoxical thought of the unthinkable takes place” (Thacker 2011, 2). The genre highlights a non-human or without-human as a creeping other narrative that illuminates itself through the mediated portals and passages between natural and supernatural realities – two contrasting worlds somehow existing simultaneously. This paradox is essential to supernatural horror for genre writer Thomas Ligotti. In his nonfiction work on the philosophy of pessimism, Ligotti discusses supernatural horror as a confrontation where one “must face down or collapse in horror before this ontological perversion – something which should not be, yet is…What is exceedingly material resides in the supernatural horror that such beings could exist in their impossible way for an instant” (Ligotti 16). In order for the paradoxical of supernatural horror to convince us of its own reality, it must interact with the rational and natural human world. Though some texts stay within the expectations of genre, supernatural horror allows texts the ability to highlight their own natural realness by the manipulation of their form and break down their diegetic realities. As a consumable media object, horror “give[s] consistency (mood) to an imagined world in which we can at least pretend to escape from our mere humanity and enter into spaces where the human has no place and dies to itself either weeping or screaming in awe at the horror of existence” (Ligotti 184). In Unfriended, the interaction of these paradoxical spaces happens on multiple levels. The ghost interacts with human beings through instant messaging online, its presence causes physical actions in its victims, and technology fails to maintain its consistent control over its hardware and software.

This extension of the supernatural beyond the limits of diegetic space degrades the limitation of the film’s narrative constraints of its own horror. This suggests a breakdown of cinematic form, of the “corresponding generic techniques [that] have been devised for reflecting and artistically processing such appropriated aspects of reality” (Bakhtin 84). This representation of the form of narrative is the “chronotope” – “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature” (ibid). By extending this idea to film, we have separated diegetic and extradiegetic narrative elements, each with their own temporal and spatial qualities, representing a combined cinematic experience. The chronotope of film represents a specific form and logic to cinematic structures and the display of narrative. Unfriended is not just a supernatural horror film, but a horror film that is presenting itself supernaturally. Therefore, the supernaturally layered diegesis frames a horror that is not just the cinematic representation of fear, but rather the control over form and narrative representation. By manipulating the logics of cinematic chronotopes, the film is able to structurally embed the paradoxical.

As much of Unfriended takes place through the abstraction of interaction through digital means, it is important to establish that space as natural and dominant for the setting of the film. The supernatural requires a paradoxical relationship to natural existence. While the ghost of the film interacts physically with the characters (usually in the form of their suicides), its primary manifestation is in its digital presence. As the film’s diegetic space is the digital representation of programs and visual abstractions of characters and their bedrooms, Unfriended relies on the use of social media as a way of constructing an environment for narrative interaction. Social media and digital profiles represent a form of “networked publics” where “spaces and audiences are bound together through technological networks (i.e. the Internet, mobile networks, etc.). Networked publics are one type of mediated public, the networked mediates the interactions between members of the public” (boyd 8). Facebook profiles, YouTube accounts, and Instagram pages represent spaces that expand upon the story of Laura’s life and suicide, as well as spaces of interaction with the ghost. The teenagers in the film have public spaces for audiences to consume and use these to form a sense of identity. As much of the background drama happens through the use of social media, the main characters’ involvement in Laura’s death slowly gets uncovered. As much of the content about Laura is accessible by anyone, the space of the film calls to attention structures of knowledge pertaining to her life – “privacy is not about structural limitations to access, it is about being able to limit access through social conventions. This approach makes sense if you recognize that networked publics make it nearly impossible to have structurally enforced borders” (boyd 15). This lack of borders is important for how information is spread in the film, but also for how the ghost is able to interact within and manipulate these digital spaces. While there is no physical space to consider for the film, we must consider how the supernatural interacts with the “naturalness” of the digital – “Instead of regarding [social networking sites] as simply a means to communication between two given localities, it is also possible to start thinking about SNS as places in which people in some sense actually live” (Miller 156). These programs and websites become the lived space of the film.

As the digital relies on technology to exist, this construction of spatiality is present in the form of data via programming, user interaction, and physical containment. Because of these varieties of forms, the presence of the supernatural requires careful consideration. The corruption of data serves as a primary indicator of the ghost’s presence. The video and audio streams jumble with noise as image fractures and sound distorts. By representing the ghost in the form of corrupt data, the film asserts the presence of the spirit within the binary code being transmitted between computers across networks – the ghost is able to touch and manipulate the 1s and 0s of information. The ghost within the data embodies a breakdown of the reliability of software, where successful transmission is a given – “This forced binary imposes a kind of violence, one that demands a rationalization of all singularities of expression within a totalizing system” (Nunes 5). The Skype windows serve as spaces of controlled communication, where the friends can be private with each other without the “public” aspect of other social media. The presence of the ghost corrupts this sense of control by being a user that cannot be removed from the chat and by degrading the quality of the conversation through distortion. By using recognizable programs and practices of social media, Unfriended projects a sense of control over software by users and the audience. When things go wrong, however, that control is shattered. This sense of loss is jarring, as “we anticipate consistency in our mass-produced products, dependability in our 24/7 connectivity, and quality assurance in our customer service. Within this dominant ideology, the unfortunate outcomes of error serve only one purpose: to remind us of the need for greater control” (ibid). When Ken tries to send his friends a virus scanner without the knowledge of the ghost, he attempts to regain control over the software and user experience. But, as the ghost is a corruption of this sense of control over data, and enforces its own paradoxical control over the experience of others, the attempt to regain power results in Ken’s violent death. The noise present on screen is a reminder of this shift in power.

The sounds of received instant messages become audio cues of the ghost’s presence and serves as a way to interact with the user in the background of the main action. While this allows for scene transitions to occur when a program window shifts to the front of the screen, it also brings the audience’s attention to other aspects of the narrative by alerting them of messages from the ghost that lead to story development. As the framing of the film is that of a computer screen, the cinema or television (etc.) screen becomes representational of the computer and its surroundings that of a desk or user environment. The audience shares the same visual perspective of the computer user and the audio cues serve as a reactionary signal that something is happening somewhere else. As shared users of this computer experience, Blaire and the audience must tactically engage the computer screen. This framing of diegesis provides a cinematic experience where “the audience has become a worker” (Evans 112), or in the case of Unfriended, and unwilling participant with a group of friends online. As Blaire shuffles through program screens, instant messages, the group chat, and informative website on the supernatural, the audience must also carefully discover information that may otherwise not be immediately voiced by the film. While talking to Mitch or attempting to learn about hauntings, Blaire is quickly distracted by the sound of an incoming message. This sound breaks the momentum of investigation. The ghost exists both as a contrasting computer user and as a supernatural element that is manipulating the flow of narrative. The audience is a passive user, but is also under this control. When the hard drive clicks or the chat stream breaks down, we know that it is something directly relating to the ghost or of Laura’s story. This struggle for user control over the narrative is moot, as the supernatural “manifests itself to us in the ambivalent ways, more often than not our response is to recuperate that non-human world into whatever the dominant, human-centric worldview is at the time” (Thacker 2011, 4). While Blaire and the audience attempt to regain the computer experience, the supernatural is able to maintain its control. By using audio manipulations as a means to signal Blaire or the audience in one direction or another, this experience frustrates the diegetic presentation of narrative.

By establishing the digital as the natural setting, the supernatural can now paradoxically exist in relation to it. It lives in technology and in spite of it. By employing means of supernatural manipulation and interaction through both digital and “in real life” methods, the film sets up a way for the spirit to transcend the natural space of the digital and physical spaces. This provides a way for the ghost to exist in multiple forms simultaneously, adding to its paradoxical form. The ghost is present in the bedrooms of the teenagers, in the binary data of communication and social media, in telephone call to the 911 operator, and in the extradiegetic audio for the audience. While the characters of the film are non-corporeal in the sense that we only seem them as digital abstractions in a video chat, that are still visually represented as bodies. The ghost simultaneously lacks corporeal form and lacks the ability to be contained within specific narrative elements. The figure of the faded body representing the ghost is a trope for horror cinema, reaffirming a corporeal state of being after death and a cephalic connection to reason and thinking; the spirit-as-identifiable cephalic object reaffirms “not only the seat of reason and cognition, but the privileged place-holder of the human as well” (Thacker 2014, 15). Without a visual representation, the ghost denies the audience any form identification or understanding of the supernatural. The denial of this knowledge secures the film’s supernatural power, as “the moment we think it and attempt to act on it, it ceases to be the world-in-itself and becomes the world-for-us. A significant part of this paradoxical world-in-itself is grounded by scientific inquiry – both the production of scientific knowledge of the world and the technical means of acting on and intervening in the world” (Thacker 2011, 5). The ghost as supernatural element, and the presentation of the film as supernatural structure eliminate the possibility to control the flow of narrative by way of program windows or the use of computer as a way of asserting control over life. The ghost collapses the digital space of the natural world and the characters’ use of the computer by way of supernatural dominance over the diegesis in a radically unhuman way.

This control by refusal of containment extends itself to the extradiegetic audio of the film. As the audible hard drive clicking noises are present but unheard in Blaire’s room and outside of the digital presentation of the computer screen, these noises lack both diegetic inclusion and physical containment by the laptop’s hardware. Transcending both the limitations of software and hardware, “this ‘thing’ is really a no-thing, insubstantial and without determinate form, and yet omnipresent and omnivorous. The ‘thing’ has no body, is not composed of any substance, and it cannot be identified by simply pointing to it or even by naming it” (Thacker 2014, 16). Its containment, identification, and natural logics all fail, and by association, so does the chronotope of the film. As the film presents it as extradiegetic information, the noise of hardware signifies specters of being, but only for the audience to fleetingly identify on the soundscape and associate with diegetic information. While describing the noise made by the medical equipment in The Exorcist, Mark Evans states that “Given that these are machines, controlled not by haphazard decisions but via programmed sequences, their aural contribution to the film is most unsettling” (Evans 117). These machines are scanning the body of someone possessed by a demon, and failing to maintain their programmed state. However, in Unfriended, the computer is not trying to analysis the possessed, but becomes possessed itself. This expression of disorder on an otherwise orderly technology presents an unsettling lack of control of diegetic machine and extradiegetic bearer of cinematic space. It becomes the “voice” of the ghost (represented in audio, as opposed to its text conversations) and something that can only be heard by the audience.

As the disk inside the hard drive continually spins in order for information to be read and displayed by the computer, it breaks down the boundaries between the supernatural and natural worlds. By metaphor, the storage disk serves as a “magic circle,” a “boundary between the natural and supernatural, and the possible mediations between them that are made possible by the circle itself. Hence the magic circle is not only a boundary, but also a passage, a gateway, a portal” (Thacker 2011, 55). As a piece of storage technology in a computer, the hard drive disk spins at high speeds as an arm stretches across and reads sectors of information. This allows for the operating system to be stored and for software to be installed and launched. The data necessary to open an internet browser or have a group Skype chat is necessarily stored and read from the disc. The ghost’s presence as a glitch in the software implies that the storage system has become a boundary for the supernatural to extend across digital and analog forms. For the user, it is the space of natural interaction with the digital. It is the portal for the supernatural to exist in the natural world, and for the ghost to be digital glitch and physical noise. But also, it functions as a “dissolving of the boundary between natural and supernatural, the four-dimensional and the other-dimension, the world revealed and the world as hidden” (ibid 75). The clicking hard drive demonstrates how the limitations of technology and our control over it become apparent when confronted with the paradoxical otherness of the supernatural. Hardware is still limited to the logics of the natural world that created it, and the Click of Death signifies the eventual failure of the technology-as-portal. When that failure finally presents itself visually, the supernatural not only ceases the display of the computer screen diegesis, but Blaire’s life as well.

As the film concludes, the diegetic layers are cinematically smashed down into one final dimensional representation. Not only are we given a look at the “real world” of Blaire’s bedroom, but of the only image of the ghost. While this moment lasts a few short seconds, its narrative power is conclusive – computer death, bodily death, and the natural exposure of the paradox of supernatural existence. For a few seconds before the final credits, all previously known narrative space collapses on itself. After everyone else’s suicide, Blaire finally confesses to the worst grievance of all her friends. Vengeance is complete, as the supernatural accomplishes its assertion over Blaire’s life. In this moment we see how the supernatural is not simply limited to the technology-as-portal, and perhaps never actually was. Instead, the film served as a game for its interaction with the natural world. The film is shifted away from its nontraditional digital presentation and back to the world of standard cinematic view. That is a powerful shift, because for this particular movie, its chronotope is structured to be the digital view of a screen. As the audience is ripped away from that view and that particular diegetic layer, the supernatural has successfully invaded the ever-corrupted natural world. While this provides the film’s only “jump scare” tactic, its jarring juxtaposition of the audience’s experience is more powerful. As we finally see the film’s credits, we are reminded of their lack at the beginning. Here is the audience’s reminder of the film-as-film, rather than digital interactions of a group of friends with the supernatural. The last sound the audience hears is the scream of the ghost, whose voice is no longer limited to the text of chat windows and technological corruption failing hardware.

By breaking down the layers of narrative construction, Unfriended creates a filmic experience where the supernatural is able to haunt the spatial representations natural world of the film and the experience of the audience. As audio transcends from the diegetic noises of the film’s ghost to a layering of haunted audio for the viewer, the horror of the film shifts from elements of genre to form. Through the use of an abstract digital setting made spatial through the lived experience of the teenage characters, the world of social media and computer programs builds a cinematic landscape where hauntings escape the single physical locations of genre horror. Webcam streams limit the visibility of characters, but their social interactions in a digital setting create a spatial world of teenage habitation. As the safety and security of social media environments breaks down, the supernatural paradoxically exists in the glitches, the instances of audio and visual data corrupted and incomprehensible by both technology and human. This force defies the logics of containment, as it exhibits control over multiple medias, program platforms, technologies, and the form of the film itself, as it extends itself into extradiegetic information. By framing the film within a viewable screen, the audience shares the view of the participants and are given elements of horror just for their consumption. While Unfriended is a part of the teen horror genre, its unique construction offers more than the story of characters visited by a vengeful spirit. By considering this film’s form, one can look at its horror not through a list of genre essentials, but through the structural manipulations of the film’s diegetic and extradiegetic narrative elements.

Works Cited –

- Bakhtin, M. M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: U of Texas, 1981. Print.

- boyd, dana. “Why Youth (Heart) Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life”. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning – Youth, Identity, and Digital Media Volume. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

- “E/n.” Everything2. Everything2, 09 Aug. 2001. Web. 20 May 2016. http://everything2.com/title/e%252Fn.

- Evans, Mark. “Rhythms of Evil: Exorcising Sound from The Exorcist.” Terror Tracks: Music, Sound and Horror Cinema. Ed. Philip Hayward. London: Equinox, 2009. 112-24. Print.

- “GRC | What IS the “Click of Death”? .” GRC | What IS the “Click of Death”. Gibson Research Corporation, 04 May 2013. Web. 13 May 2016. https://www.grc.com/tip/codfaq1.htm.

- Ligotti, Thomas. The Conspiracy against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. New York: Hippocampus, 2010. Print.

- Miller, Daniel. “Social Networking Sites.” Digital Anthropology. Ed. Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller. London: Berg, 2012. 146-61. Print.

- Nunes, Mark. “Error, Noise, and Potential: The Outside of Purpose.” Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures. Ed. Mark Nunes. New York: Continuum, 2011. 3-23. Print.

- Thacker, Eugene. In the Dust of This Planet. Winchester, UK: Zero, 2011. Print.

- Thacker, Eugene. “Thing and No-Thing.” And They Were Two in One and One in Two. Ed. Nicola Masciandaro and Eugene Thacker. N.p.: Schism, 2014. 10-30. Print.

Further Reading:

Bloody Disgusting just recently put out a nice little article about the film as well https://bloody-disgusting.com/editorials/3808461/unfriended-one-of-the-best-screenlife-horror-movies-turns-10-this-year/