John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness (1995) represents one of the last horror movies by the acclaimed director, who only worked on five more feature films of various genres up until the current day. The film itself, though barely profitable (IMDB), would go on to gather critical and cult praise, including being considered one of the top films of its year by the Cahier du Cinema (Johnson). The film follows the investigation by John Trent (Sam Neill) into the disappearance of the reclusive horror writer Sutter Kane (Jurgen Prochnow), who is the most widely published and read author on the planet. Kane’s publishing company is expecting his final book, and sends Trent and Kane’s editor Linda Styles (Julie Carmen) to attempt to find the whereabouts of the writer. When Trent finds a map that leads to the fictional town represented in Kane’s writings, he believes that his investigation is a part of an elaborate scam by the publishing company. After driving to the location, his stay in the town of “Hobb’s End” becomes increasingly weird, as events and characters from Kane’s work begin to present themselves as reality. After escaping the fictional world of Kane’s writing, Trent hopes to find himself back himself back in the familiar surroundings of New York City, only to learn that the horrific power in Kane’s writing has begun to infect the reality of the world. As a horror film, In the Mouth of Madness expresses several paradoxes throughout its duration. While this process takes place within the film’s story as monsters assert themselves into the reality of the main characters, it also is represented through the use of conflicting narrative spaces within the film’s diegesis. A noticeable visual pattern signals a shift in setting as characters shift from one narrative space to another. The narrative space of the film becomes increasingly abstract and porous, as characters shift between these spaces, sometimes without their own knowledge or consent. This transference comes to a climax as Trent is seen running on an abstract bridge away from the fictional-turn-real horrors of Kane’s writing. As exemplified through an examination of these transitions and abstract spaces, In the Mouth of Madness’s use of paradoxes and their tensions within its diegesis creates a sense of disorientation for the audience through its narrative immersion.

As a work of the horror genre, In the Mouth of Madness exhibits a series of paradoxes that create narrative conflict through their confrontation. These paradoxes are in part the supernatural power of Sutter Kane and his writing, but also primarily through the existence of conflicting narrative spaces that John Trent and Linda Styles travel between. As such, the genre hinges on the unknowable realities represented in the particular media. This essential aspect establishes the genre as “a privileged site in which this paradoxical thought of the unthinkable takes place” (Thacker 2). It presents a reality not-for-us, where humanity concedes of itself as the bearers of knowledge, consciousness, and control. The genre highlights a non-human or without-human as dominate narrative and illuminates itself through the mediated portals and passages between natural and supernatural realities. The task of supernatural horror is to convince us of its own impossibility. Noel Carroll differentiates horror from science fiction and “tales of terror” by stating that “in works of horror, the humans regard the monsters they meet as abnormal, as disturbances in the natural order” (Carroll 16). Monsters, in whatever form they appear, represent a tangible experience between knowable and unknowable, creating a tension between the paradoxical representation of both simultaneously. Tzvetan Todorov describes this experience of paradoxical realities in horror as “the fantastic”, he writes:

In a world which is indeed our world, the one we know…there occurs an event which cannot be explained by the laws of this same familiar world. The person who experiences the event must opt for two possible solutions: either he is the victim of an illusion of the senses…or else the even has indeed taken places, it is an integral part of reality – but then this reality is controlled by laws unknown to us. The fantastic occupies the duration of this uncertainty…The fantastic is that hesitation experience by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event.

(Todorov 25)

Horror represents the ability for the impossible to paradoxically exist alongside reality in a horrific way. Further, these confrontations create an affective response of tension, a hesitation of consideration at the possibilities and potentials exhibited by the presentation of paradoxes. This tension exists both narratively, through the conflict within the text, and within the audience as well, as successful horror can create an (often negative) emotional response.

In the film, these paradoxes exist primarily through the ability of Sutter Kane’s books to have actual impact on the reality of the readers. As characters in the film go through violent bouts of insanity, Linda Styles explains that “Kane’s writing has been known to have an effect on his less stable readers – disorientation, memory loss, extreme paranoid reaction” (Carpenter). Styles later explains that Kane’s reclusive nature is in part due to his belief that his writing is becoming fact, and not merely fiction. For Kane’s readers in the film, this suggests an intense experience of immersion.

In the film, Sutter Kane serves as a fictionalized, modern, and successful version of the author H.P. Lovecraft – a major influence on the work of John Carpenter (Grey). To understand the impact of Sutter Kane’s writing, it is important to briefly consider the work of Lovecraft. The worldview of Lovecraft was paradoxical, as his concerns were of “cosmic pessimism” and the antiquarian (Joshi 1). An avid reader, Lovecraft was struck by the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, bringing his philosophy into his tales of the weird. The “cosmic pessimism” of his work suggested “the inconsequentiality of mankind in an aimless cosmos” and contrasting with how “all we have to fall back on is tradition” (ibid 100). That humanity was inconsequential, yet its past bearing so much importance proves quite paradoxical, and yet it is the fueling drive of Lovecraft’s philosophy and his efforts as both a writer and an antiquarian. This was often the focus of the protagonists of his stories, as well. His stories, frequently epistolary in nature, focus on the protagonist (often nameless) recanting their exposure to a horrific reality generally in the form of a letter or journal. Jon Thiem suggests that narratives, particularly easily comprehensible ones, can allow consumers to become “lost” within worlds of stories, “when the world of a text literally intrudes into the extratextual or reader’s world”, calling this process “textualization” (Thiem 339). Thiem uses Victor Nell’s study and terminology of “ludic reading” to emphasize this, as simple reading can allow for trances similar to dream states (ibid 342). During this, the reader “loses that minimal detachment that keeps him or her out of the world of the text” (ibid 343). For Thiem, much of this is due to a process of identification, and is accomplished through texts with “a pronounced metafictional dimension” (ibid.). For Lovecraft, and ergo Kane, this immersion is accomplished by the main characters being nameless and often scantily described, serving as blank canvases for the reader to project themselves onto. As epistolary works, the stories therefore serve as reflections or memories for the reader, rather than a traditionally unfolding narrative. Noel Carroll furthers this idea of immersion with horror in general, stating that it “appears to be one of those genres in which the emotive responses of the audience, ideally, run parallel to the emotions of the characters. Indeed, in works of horror, the responses of characters often seem to cue the emotional responses of the audiences” (Carroll 17).

While Carpenter’s film provides a rich text for analysis, of particular interest are the different spaces of narrative reality, the characters’ transitions between these spaces, and the impact these spaces and transitions have in terms of spectatorship. Carpenter’s subtlety and spacing of these transitions, as well as their intent, helps to build their filmic power. Some of these narrative spaces exist in a normative sense. As John Trent read’s Sutter Kane’s writing for the first time, he experiences nightmares. In this instance, Trent serves as an audience to Kane’s work, and experiences it, as Noel Carroll suggests, through a disturbance of fictional emotion, as “the audience knows that the object of art-horror does not exist before them. The audience is only reacting to the thought that such and such an impure being might exist” (Carroll 189). As Trent jokes about the power of Kane’s work and its ability to “get into your head,” Trent’s experience is that of a typical horror reader, and the audience experiences a sense of identification with Trent’s character. These dream scenes early in the film represent the first instances of transference between narrative spaces and the first instances demonstrating the power of Sutter Kane as a supernatural villain. The banality of experiencing fear from a horror text, to have a bad dream, is a recognizable experience – something that extends the character of John Trent’s identifiability as someone who feels the impact of a horror-text’s narrative. Through this early instance of transfer through narrative space, and Trent’s identifiable reaction to it, the audience of the film can gain an early sense of identification and immersion. Following Thiem’s idea of textualization and Carroll’s concept of emotional identification, the audience begins to share the sense of disorientation as they are jarred between the world of a dream and Trent’s reality.

A visual representation of transitions and narrative space. (By me)

This disorientation is extended further through the film, and through more jarring instances, as the characters are transferred not simply to the space of dreams, but into the actual space of Kane’s fiction – into the fictional city of Hobb’s End. After solving a puzzle hidden on Kane’s book covers that gives the location of Hobb’s End, New Hampshire (which does not exist), Trent and Styles drive to find Kane and his novel due for publication. As day turns to night, Styles takes over the driving duties so that Trent may sleep. The dashed yellow lines on the street offer a hypnotic repetition and Styles blinks hard to concentrate on the road. As these familiar lines vanish, a worried Styles checks out the window for her position on the road. The car is seen driving on a purely black surface that is soon illuminated by lightning to show that the car is now, somehow, on top of storm clouds. The wheels connect onto an old wooden bridge and the lightning flashes continue to strobe. Styles looks out the window to see solid black walls with oval-shaped holes shining brightly with white light. These holes rhythmically pass by and Styles blinks hard once more. The car is now surrounded by the wooden slats of a covered bridge with natural sunlight shining through. Carpenter assertively contrasts the visuals of the wooden bridge with that of a film strip’s sprocket holes to emphasize their narrative significance. This is a transitionary space between two very different narrative realities, and the meta-textual reference helps to emphasize the disorientation due to this crossing over.

Differentiating between the established views of the bridge.

Disoriented by the experience, Styles passes through the covered bridge into the brightness of morning in Hobb’s End and Trent wakes up from his sleep. Styles and the audience have transferred from the reality of the previously established world into the abstract space of the fictional Hobb’s End. Due to Trent being asleep, he can only assume they have arrived at a small New England town that Kane has set up to market his final book. How the characters have transferred from the fictional-but-real-to-them world of the film to the entirely-fictional and abstract world of Hobb’s End is in part due to Carpenter’s creation of a hyper-narrative filmic text – an alternative narrative space running parallel to the previously established setting. This is established as filmic texts “shifts between alternative or optional narrative threads that lead to different outcomes or temporal configurations” (Ben-Shaul 33). While the ultimate narrative outcome of the film will eventually be achieved, it can only be done through the transference from the established reality of the filmic New York into the textual fiction of Sutter Kane’s writing.

As this begins to test Styles’s sanity, Trent is initially unphased. As Styles had witnessed a shift in her orientation to reality by crossing the literal and symbolic bridge across narrative spaces, Trent was fast asleep. The audience can once again identify with Trent as his sleeping through the event mirrors the audience’s uncertainty as to what has just occurred. This again marks a sense of textualization – of deeper engagement with the text – established previously. Thiem furthers the establishment of textualization by suggesting that it is accomplished initially by, “a reader or sometimes an author, or even a nonreader, will be literally, and therefore magically, transported into the world of a text” (Thiem 339). As Trent serves as a proxy for the audience’s uncertainty of their experience, their engagement with the “world of a text” can be further emphasized by In the Mouth of Madness through Trent’s continued experience within Kane’s fictional world and power.

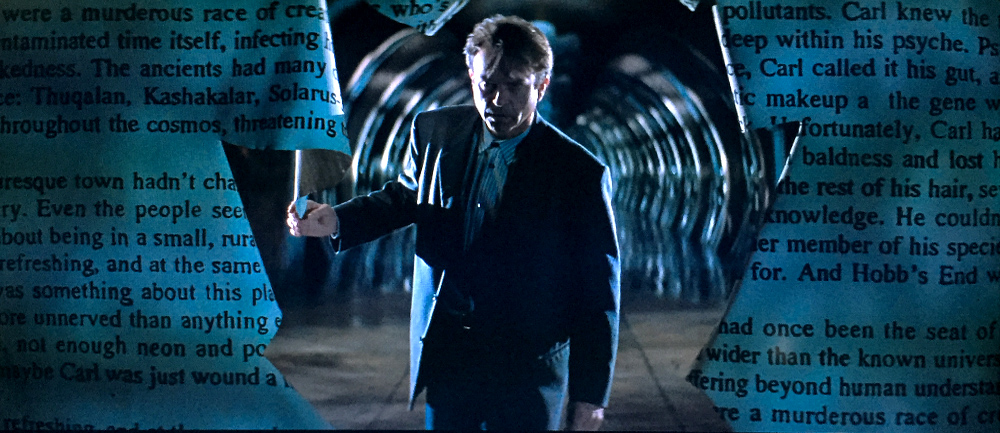

As their experience in Hobb’s End grows increasingly weird and dangerous, Trent and Styles attempt to flee Kane. Their actions prove powerless as Kane is the creator of the fictional world they inhabit. Trent is soon brought to the abandoned church in town where Kane has secured himself. He wakes up in a panic in a dimly lighted room with walls that resemble muscle membrane, as Kane sits at a desk typing at a typewriter. He is finishing his novel. While one presumes that Trent and Kane are still in the church, the room is abstract. Trent and the audience do not know where they are, other than in Kane’s room. Kane hands Trent the finished manuscript of his not coincidentally named novel In the Mouth of Madness and walks towards a large wooden door, secured with chains, that is rattling from what is behind it. Kane tells Trent that he is merely a part of this novel, a fictional construct under the power of Kane’s writing, as is all things in Hobb’s End. He tells Trent to “Go back. Your world lies beyond that passage” and to deliver the manuscript to the publisher (Carpenter). Kane’s room serves as a portal space – a liminal setting between the world of his fiction and the reality represented earlier in the film. As a portal, this space “serves as a boundary between the natural and the supernatural, and the possible mediations between them” (Thacker 55). As such, the abstract space of Kane’s room serves as a “magic space” – “the place where the hiddenness of the world presents itself in its paradoxical way (revealing itself as hidden)” (ibid. 82). This paradox creates a horrific experience for Trent and the audience. Jarkko Toikkanen emphasizes this by stating “when one meets something that so stuns the mind, generates an aesthetic experience that literally stops the individual in one’s tracks, there is ‘some degree of horror’” (Toikkanen 10). The audience and Kane are experiencing an abstract space and new realities. As the immensity of this abstraction disorientates Trent, the audience too is increasingly disoriented. We no longer know where exactly we are, or the implication of our leaving. As we continue to define horror through the confrontation of these paradoxes, Kane commands Trent to leave through “the passage” and that he “can’t hold them back any longer” (Carpenter). The wooden door begins to break down and Kane tears away at the represented space of the film itself, exposing a black abyss behind him.

The frays of the tear peel down, exposing the other side of the filmic space – it is the pages of Kane’s writing represented in the form of a published book. On one side of this reality is the represented cinematic space of Kane’s room and the film itself and immediately on the other side are the pages of Kane’s fictional novel. But, as the hole widens, the abyss beyond stirs with movement. The nameless monsters of Kane’s work emerge through the whole and chase Trent down the “passage”. The monsters and monstrous abyss seem to represent a different abstract space altogether – one of horror-as-reality that gives truth and power to Kane’s writing. As these monsters chase down Trent, we are seeing a merging of horror-as-reality, through the fiction of Kane’s writing, with the established reality of the film. Thacker asserts this thematic occurrence as strongly present in the work of Lovecraft, where a “dissolving of boundaries between the natural and supernatural” which “bizarrely flattens all dimensions into one” (Thacker 75). This flattening by way of horror-fiction-reality unification serves as an immersive strategy for Carpenter’s horror, against invoking Thiem’s sense of textualization, where “a second type of textualization takes place when the world of a text literally intrudes into the extratextual or reader’s world” (339). The fictional world of Kane’s writing is literally intruding into the reality of Trent-as-reader, and creating an immersive and horrific filmic sensation for the film’s audience-as-Trent.

This “passage” shares similar aesthetic qualities as the filmstrip-bridge that Styles witnesses while driving into Hobb’s End. We again see the repetitive oval pockets of light, reminding us of a film strip’s sprocket holes. As that experience serves as the end of Styles’s reliable sanity, Trent’s avoidance of this moment due to his sleeping is experienced here by way of his journey back across this abstract passageway between narrative spaces. As established earlier, John’s lack of experience and the audience’s uncertainty of it evokes a sense of shared engagement with this abstract narrative bridge. The audience does not share the intensity of Styles’s transference. Because of Trent’s position as the protagonist, his sleeping, and lack of knowledge of the narrative crossover mimics that of the audience. As the audience’s experience is marked by Trent’s this second exposure emphasizes the sense of immersion between these narrative and abstract spaces. With Styles, we unknowingly share Trent’s switch into the unknown. However, because of the repetition of this experience, the audience can determine what has happened, as one compares these two scenes through hindsight. Now as Trent runs back across this abstract bridge/passage, the audience knowingly runs away from the unknown. But to where?

As Trent stumbles through a series of disorienting scenes, he thinks he is fleeing Kane and his power. The disembodied voice of Kane assures Trent that he has no choice but to follow the path that was written for him. This space represents Kane’s Manipulated Space – an almost hallucination of Trent’s, except that he is really experiencing it. We don’t know where we are, nor does Trent or the audience have any agency over what transpires during this filmic transition. We are no longer in the fictional world of Hobb’s End, nor are we back in the concrete reality of Trent’s New York. We are lost in an abstract narrative space and because Kane holds all the power over Trent’s experience, the audience is also subjected to this power. This shifts the power of horror in the film away from the experience of the paradoxes of contrasting narrative spaces towards a paradox of personal experience. The audience is subjected to a series of unrelated scenes of Trent’s attempted escape – on bus, in a motel, on the side of the road, etc. These scenes all end with the reassertion of Kane’s power over the narrative and cut jarringly into each other. There is no transition, literal or cinematic. The paradoxes represent a personal sense of disorientation, rather than a narrative one, as Dylan Trigg emphasizes that “this inversion of horror, together with Carpenter’s violation of the fourth wall, is not contained within the film itself, but instead dissolves the very boundaries between the spectator and the spectacle” (Trigg 93-94). Todorov’s “hesitation” experienced by the audience is no longer limited to the confrontation of paradoxes, but rather in the decay of the expectations of the text itself – a paradox of consumption.

The film itself ends with Trent back in the previously established reality of the opening scenes, though now infected further by Kane’s work. While he attempted to stop the publication of the In the Mouth of Madness novel, Kane transferred him forward in time in which the book has been out for months. In this post-Kane world, riots are beginning to spread across the country. Trent’s sanity finally breaks, and after a violent outburst, he is sent to an institution with the knowledge that the film adaptation of the novel is set to debut worldwide in a few days. While in his cell, society crumbles, as represented by shadows and noises happening outside his cell walls. He wakes to find his door open, the institution empty and in shambles, and he walks out the front door in his medical gown. The city streets are filled with the remnants of struggle, but there are no people, as if Trent has slept through the end of the world. He walks to a nearby movie theater playing the adaptation of the novel, only to see that it is the movie the actual audience has just watched, and John Trent’s life as film. As the film plays on, Trent can only eat popcorn and laugh at what is on display before him. By connecting the beginning of the narrative spatially with the end, while contrasting it across a variety of narrative spaces and potentials in the middle, the film’s engagement allows for a “salience of this obligatory first framework [that] can be exploited for imparting a sense of succession to following optional narrative threads by maintaining some of its components as invariables” (Ben-Shaul 34). By making the narrative spatially recursive, the contrast of the normativity of the beginning adds to the power of the extended weirdness and horrific qualities of the succeeding narrative threads.

By commenting on the text as a meta-textual object, where Trent is seen watching the film In the Mouth of Madness, which is the same text as the filmic audience, the horror exists in an immersive and engaging context. The narrative itself becomes a paradox of its own. Existing in different contrasting forms simultaneously, the film itself becomes a horror object, rather than a genre film. This accomplishment in what Carroll refers to as “one effect of (perhaps) relatively high achievement within the horror genre” which signifies a sense of “awe” or a “numinous experience” where a text can achieve something “tremendous, causing fear in the subject, a paralyzing sense of being overpowered, of being dependent, of being nothing, of being worthless” (Carroll 164, 165). By using paradoxes and engaging the audience through textualization, “horror is not restricted to the frame of the cinema, but instead bleeds through the medium, infecting both us and those who come into contact with us in the process” (Trigg 94). By creating a transitory experience between realistic and abstract narrative spaces, for characters and the audience alike, Carpenter can extend the experience of “hesitation” into an immersive horror text.

Works Cited

- Ben-Shaul, Nitzan S. Hyper-narrative Interactive Cinema: Problems and Solutions. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008. Print.

- Carroll, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror, Or, Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge, 1990. Print.

- Grey, Orrin. “Cosmic Horror in John Carpenter’s “Apocalypse Trilogy”” Strange Horizons. Strange Horizons, 23 Oct. 2011. Web. 14 Dec. 2016. http://strangehorizons.com/2011/10/24/cosmic-horror-in-john-carpenters-apocalypse-trilogy/.

- In the Mouth of Madness. Dir. John Carpenter. Warner Brothers, 1995. Blu-ray.

- “In the Moutth of Madness.” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2016. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0113409/.

- Johnson, Eric. “Cahiers Du Cinema.” Cahiers Du Cinema: Top Ten Lists 1951-2009. N.p., 03 Jan. 2013. Web. 14 Dec. 2016. http://alumnus.caltech.edu/~ejohnson/critics/cahiers.html.

- Joshi, S. T. H.P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West. Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House, 1990. Print.

- Thacker, Eugene. In the Dust of This Planet. Winchester, UK: Zero, 2011. Print.

- Thiem, Jon. “The Textualization of the Reader in Magical Realist Fiction.” Essentials of the Theory of Fiction. By Michael J. Hoffman and Patrick D. Murphy. Durham: Duke UP, 1988. 339-50. Print.

- Todorov, Tzvetan. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Cleveland: Press of Case Western Reserve U, 1973. Print.

- Toikkanen, Jarkko. The Intermedial Experience of Horror: Suspended Failures. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Print.

- Trigg, Dylan. The Thing: A Phenomenology of Horror. Winchester, UK: Zero, 2014. Print.